"The long stone wall receding into the distance, the words that require me to lean forward and peer closely at them, the gravel beneath my feet, even the air laden with traffic fumes – everything has a weight here, pressing me down. As I stand in front of the names, I feel on display, considered by a silent audience. There is only one of me and so, so many of them." |

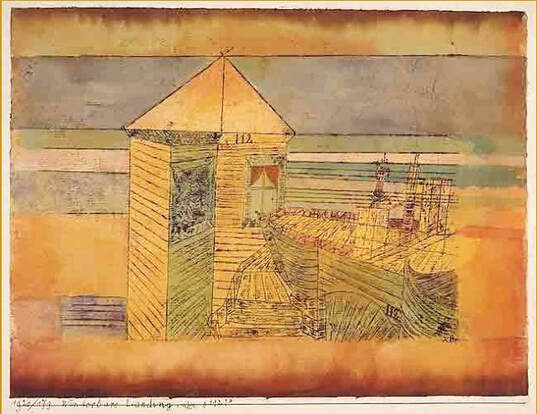

Paul Klee, Miraculous Landing, 1920

Paul Klee, Miraculous Landing, 1920

A ferry travelling across the North Sea must take account of the tides, the twice-a-day ebbing and flowing of the sea that is caused by the Moon’s orbit around the Earth. At every port along these coasts, including those identified in my grandfather’s German passport, the timing of the tides will affect the precise route of the ferry and the complex manoeuvres needed to bring it safely to land.

My grandfather made the journey across this water that divides England from continental Europe on at least three occasions, recorded by the immigration authorities when he reached England. The dates and locations of his arrivals are stamped in ink in his passport:

12 Sept 36 Harwich

5 Sept 37 Harwich

6 Sept 38 Newhaven

What I find curious about these dates is their periodicity. Each year shortly before the autumnal equinox, my grandfather left his temporary residence in London and travelled to his original home in Germany for a few weeks, before returning. These journeys back east could be considered to be regressive or retrograde motions, like those that become apparent when we observe the orbits of planets.

The word ‘planet’ itself means ‘wanderer’ in ancient Greek because, against the stable background of the stars, each of the planets can be identified by its own distinctive path. Mars is observed moving from west to east for nearly two years at a time, before appearing to rapidly reverse direction and going backwards for a period of two months, and then changing direction yet again and resuming its original path. It wasn’t until the development of the Sun-centred model of the planets’ orbits that these peculiar loops were demoted to nothing more than a visual trick, a consequence of observations being made from the Earth – whose own position is constantly shifting.

Other dates are recorded in my grandfather’s passport, providing evidence that he was living in London from 1936 onwards. Prior to that, he had spent most of his life in Germany. So why did he leave the safety of England and return to a place where he would have been in significant danger? Why did he go back to a country where the rights of Jewish people were increasingly restricted from one year to the next? In 1934, Jewish students were excluded from exams in medicine, dentistry, pharmacy and law. In 1935, with the Nuremberg laws brought into force, Jews were no longer citizens of the Reich. They could neither marry nor employ non-Jews. Their ability to obtain passports was limited. By 1938, Jewish businesses were forced to shut down and Jewish children were expelled from school.

The first person to explain Mars’ retrograde motion was the Austrian astronomer Johannes Kepler at the beginning of the 17th century. He obtained tables of observations of Mars taken over many years and recorded as a series of times and places, the date of each observation alongside the corresponding position of the planet in the sky. Positions of astronomical objects (such as stars, planets and galaxies) are written using a system that resembles longitude and latitude on Earth, the celestial equivalents are Right Ascension (RA) and declination (dec). For example, on 18 February 2021 (the day NASA rover Perseverance touched down on its surface), Mars’ coordinates were:

RA dec

03h 17m 07s +19° 38’ 20”

Kepler showed that the simplest mathematical way to describe the orbits of planets around the Sun is not with circles, but ellipses. This means that each planet’s speed varies, either slowing down or speeding up, depending on its changing distance from its star. In addition, the closer a planet’s orbit is to the Sun, the faster it must travel. Because of the Earth’s position between the Sun and Mars, as it overtakes Mars on the inside the latter appears, from our viewpoint, to move backwards.

Passports aren’t intended to be scientific documents and yet they can be analysed to provide information on journeys – their beginnings and destinations in time and space. But nothing in my grandfather’s passport, issued by the German Embassy in London in 1936, tells us the reason for his journeys.

In fact, my grandfather had already travelled west long before the 1930s. After he left school in 1916, he was conscripted into the army and served for more than two years in the trenches of northern France. These movements from east to west in 1916 and again later in the 1930s, all of them under the influence of war, remind me of Kepler’s uneasy associations with astrology. In 1601, Kepler was appointed court astrologer to the Emperor Rudolph II in Prague. He was seemingly well known for his ability to cast accurate horoscopes and yet he disliked the practice of using them to divine the future. Did Kepler, as other astrologers have done, identify Mars with war and martial ambitions, or was it simply a point of light in the sky that he could use to test his scientific ideas about planetary orbits?

My grandfather lived in England until his death in 1963. He was one of that unlucky generation required to fight in both world wars, but there must have only been a handful of men, like him, who fought in the German army against the British in the First World War, and in the British army against the Germans in the Second. Written on the page, it looks like a riddle:

If I am on a moving planet why do I feel at rest?

Why am I fighting against the country of my birth?

Were I able to travel alongside my grandfather and at the same speed as him, he would appear to be at rest. But now, considering his journeys, I have my own complex orbit to take into account. When I first started writing about him, I thought that my viewpoint wouldn’t make any difference. But of course it does, because I am now in Frankfurt, very near to where my grandfather came from. When I moved here just over two years ago, it meant that as a family we have completed an entire orbit of experience, of leaving and arriving back in the place where we started.

I have to keep asking myself why I came here because, unlike a scientific enquiry, there is no straightforward answer, or rather there are too many competing answers. He died long before I was born, so for me he only exists on paper and in anecdotes. Perhaps I wanted to walk the same streets he did. Except, of course, they are not quite the same streets. Events have intervened.

Our surname is known here. I have found it tattooed on the city, on street signs and memorials such as the Holocaust memorial built on a wall surrounding the old Jewish cemetery. This displays the names of each of the 12,000 Jewish victims of the Holocaust who originally came from Frankfurt, engraved on individual plaques a few inches across, together with birth dates, and dates and places of death – if known. This is the first time I have seen my own name written so many times. Echoed over and over again, as if being practised for some unknowable reason. A word so often repeated can lose its meaning, become unmoored from reality; no longer a symbol of someone, it is a mere collection of letters. But here GOLDSCHMIDT has attained a new status, an additional meaning. How can I write my name in the future without thinking of these people here, and the places recorded on their slates? Treblinka, Sobibor, Mauthausen, Belsen-Bergen, Buchenwald, Theresienstadt, Riga, Majdanek, Auschwitz...

The long stone wall receding into the distance, the words that require me to lean forward and peer closely at them, the gravel beneath my feet, even the air laden with traffic fumes – everything has a weight here, pressing me down. As I stand in front of the names, I feel on display, considered by a silent audience. There is only one of me and so, so many of them.

I have read my history, read about the causes of the Second World War stemming from the defeat of Germany in the First World War, the vindictive Treaty of Versailles and the French occupation of the crucially important coal seams in the Saar region, wreaking further havoc on the already damaged German economy, and ultimately leading to fascism. This is the big picture, akin to Kepler’s equations governing the planets’ orbits. But these equations are never completely accurate on small scales, because they can’t take account of every single interaction between the planets, their moons and other bodies such as asteroids and comets. This means that we don’t know Mars’ position in its orbit to an accuracy of better than 300 metres and this is why it was such an extraordinary feat for Perseverance to land safely on the surface. Like a ferry docking at a port in a rough sea, it takes some navigation skill to travel those last few metres safely.

One of the many ways in which Mars differs from the Earth is that it’s easier to see the scars left by its past; craters caused by collisions with asteroids are not eroded or covered up by vegetation and seas. Mars’ history is written on its surface in a way that is more straightforward to read than on our home planet. I still don’t know quite what I’m doing here in Frankfurt, and whether or not it can be my home, but perhaps in time I can learn to become fluent in the language of the past.

My grandfather made the journey across this water that divides England from continental Europe on at least three occasions, recorded by the immigration authorities when he reached England. The dates and locations of his arrivals are stamped in ink in his passport:

12 Sept 36 Harwich

5 Sept 37 Harwich

6 Sept 38 Newhaven

What I find curious about these dates is their periodicity. Each year shortly before the autumnal equinox, my grandfather left his temporary residence in London and travelled to his original home in Germany for a few weeks, before returning. These journeys back east could be considered to be regressive or retrograde motions, like those that become apparent when we observe the orbits of planets.

The word ‘planet’ itself means ‘wanderer’ in ancient Greek because, against the stable background of the stars, each of the planets can be identified by its own distinctive path. Mars is observed moving from west to east for nearly two years at a time, before appearing to rapidly reverse direction and going backwards for a period of two months, and then changing direction yet again and resuming its original path. It wasn’t until the development of the Sun-centred model of the planets’ orbits that these peculiar loops were demoted to nothing more than a visual trick, a consequence of observations being made from the Earth – whose own position is constantly shifting.

Other dates are recorded in my grandfather’s passport, providing evidence that he was living in London from 1936 onwards. Prior to that, he had spent most of his life in Germany. So why did he leave the safety of England and return to a place where he would have been in significant danger? Why did he go back to a country where the rights of Jewish people were increasingly restricted from one year to the next? In 1934, Jewish students were excluded from exams in medicine, dentistry, pharmacy and law. In 1935, with the Nuremberg laws brought into force, Jews were no longer citizens of the Reich. They could neither marry nor employ non-Jews. Their ability to obtain passports was limited. By 1938, Jewish businesses were forced to shut down and Jewish children were expelled from school.

The first person to explain Mars’ retrograde motion was the Austrian astronomer Johannes Kepler at the beginning of the 17th century. He obtained tables of observations of Mars taken over many years and recorded as a series of times and places, the date of each observation alongside the corresponding position of the planet in the sky. Positions of astronomical objects (such as stars, planets and galaxies) are written using a system that resembles longitude and latitude on Earth, the celestial equivalents are Right Ascension (RA) and declination (dec). For example, on 18 February 2021 (the day NASA rover Perseverance touched down on its surface), Mars’ coordinates were:

RA dec

03h 17m 07s +19° 38’ 20”

Kepler showed that the simplest mathematical way to describe the orbits of planets around the Sun is not with circles, but ellipses. This means that each planet’s speed varies, either slowing down or speeding up, depending on its changing distance from its star. In addition, the closer a planet’s orbit is to the Sun, the faster it must travel. Because of the Earth’s position between the Sun and Mars, as it overtakes Mars on the inside the latter appears, from our viewpoint, to move backwards.

Passports aren’t intended to be scientific documents and yet they can be analysed to provide information on journeys – their beginnings and destinations in time and space. But nothing in my grandfather’s passport, issued by the German Embassy in London in 1936, tells us the reason for his journeys.

In fact, my grandfather had already travelled west long before the 1930s. After he left school in 1916, he was conscripted into the army and served for more than two years in the trenches of northern France. These movements from east to west in 1916 and again later in the 1930s, all of them under the influence of war, remind me of Kepler’s uneasy associations with astrology. In 1601, Kepler was appointed court astrologer to the Emperor Rudolph II in Prague. He was seemingly well known for his ability to cast accurate horoscopes and yet he disliked the practice of using them to divine the future. Did Kepler, as other astrologers have done, identify Mars with war and martial ambitions, or was it simply a point of light in the sky that he could use to test his scientific ideas about planetary orbits?

My grandfather lived in England until his death in 1963. He was one of that unlucky generation required to fight in both world wars, but there must have only been a handful of men, like him, who fought in the German army against the British in the First World War, and in the British army against the Germans in the Second. Written on the page, it looks like a riddle:

If I am on a moving planet why do I feel at rest?

Why am I fighting against the country of my birth?

Were I able to travel alongside my grandfather and at the same speed as him, he would appear to be at rest. But now, considering his journeys, I have my own complex orbit to take into account. When I first started writing about him, I thought that my viewpoint wouldn’t make any difference. But of course it does, because I am now in Frankfurt, very near to where my grandfather came from. When I moved here just over two years ago, it meant that as a family we have completed an entire orbit of experience, of leaving and arriving back in the place where we started.

I have to keep asking myself why I came here because, unlike a scientific enquiry, there is no straightforward answer, or rather there are too many competing answers. He died long before I was born, so for me he only exists on paper and in anecdotes. Perhaps I wanted to walk the same streets he did. Except, of course, they are not quite the same streets. Events have intervened.

Our surname is known here. I have found it tattooed on the city, on street signs and memorials such as the Holocaust memorial built on a wall surrounding the old Jewish cemetery. This displays the names of each of the 12,000 Jewish victims of the Holocaust who originally came from Frankfurt, engraved on individual plaques a few inches across, together with birth dates, and dates and places of death – if known. This is the first time I have seen my own name written so many times. Echoed over and over again, as if being practised for some unknowable reason. A word so often repeated can lose its meaning, become unmoored from reality; no longer a symbol of someone, it is a mere collection of letters. But here GOLDSCHMIDT has attained a new status, an additional meaning. How can I write my name in the future without thinking of these people here, and the places recorded on their slates? Treblinka, Sobibor, Mauthausen, Belsen-Bergen, Buchenwald, Theresienstadt, Riga, Majdanek, Auschwitz...

The long stone wall receding into the distance, the words that require me to lean forward and peer closely at them, the gravel beneath my feet, even the air laden with traffic fumes – everything has a weight here, pressing me down. As I stand in front of the names, I feel on display, considered by a silent audience. There is only one of me and so, so many of them.

I have read my history, read about the causes of the Second World War stemming from the defeat of Germany in the First World War, the vindictive Treaty of Versailles and the French occupation of the crucially important coal seams in the Saar region, wreaking further havoc on the already damaged German economy, and ultimately leading to fascism. This is the big picture, akin to Kepler’s equations governing the planets’ orbits. But these equations are never completely accurate on small scales, because they can’t take account of every single interaction between the planets, their moons and other bodies such as asteroids and comets. This means that we don’t know Mars’ position in its orbit to an accuracy of better than 300 metres and this is why it was such an extraordinary feat for Perseverance to land safely on the surface. Like a ferry docking at a port in a rough sea, it takes some navigation skill to travel those last few metres safely.

One of the many ways in which Mars differs from the Earth is that it’s easier to see the scars left by its past; craters caused by collisions with asteroids are not eroded or covered up by vegetation and seas. Mars’ history is written on its surface in a way that is more straightforward to read than on our home planet. I still don’t know quite what I’m doing here in Frankfurt, and whether or not it can be my home, but perhaps in time I can learn to become fluent in the language of the past.

|

Pippa Goldschmidt lives in Scotland and Germany. She’s the author of the novel The Falling Sky, the short story collection The Need for Better Regulation of Outer Space, and co-editor (with Tania Hershman) of I Am Because You Are (all originally published by Freight Books). Her poetry, stories and non-fiction have been published in a variety of places including Gutter, Mslexia, Litro, The Scottish Review of Books, New York Times, and also broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

|