|

Marin Sorescu spoke to Allen Ginsberg in Genoa in May 1979, and to Lawrence Ferlinghetti in Mexico City in August 1982.

|

Marin Sorescu

Marin Sorescu

“The illness some of my patients suffer from,” a doctor once told me, “is caused by the fact that they forget to breathe. They get carried away with whatever it is they’re doing and fail to draw in air.”

“It also depends on the air,” I said.

“It does indeed. When forgetting to breathe, too little oxygen circulates through the body and that leads to a series of irregularities.”

“The modern man forgets to read poetry,” I added, optimistic then, as I am now, about the function of poetry. But, like air, which so often is unbreathable, does all poetry deserve to be read? Speaking of air, I hear the equatorial forest is being cut down at a speed of a thousand hectares per minute!

As so much lyricism is refreshed periodically through individual—less frequently, collective—efforts, our need is thus kept fresh due to these bouts of renewal fever.

I recalled the discussion in Mexico, meeting Lawrence Ferlinghetti for an interview. I had to go back in my mind to the experience of the Beat Generation, among whose exponents we find Charles Olson and Kenneth Rexroth, though we can’t help but detect the influence, in spirit, of Walt Whitman’s wave of humanity and vitalist frenzy as well as, in letter, the more recent one of Ezra Pound and his zigzag poetics.

Same as animals in danger group together to survive, several young American poets in the ’50s gathered in something like a lyrical pack. The word “pack” implies qualities such as mobility, hunger, action, sharp fangs, grinning, howling—epic feeling. A pack which defends by attacking. It defends poetry—their poetry, from the one that precedes it—and at the same time goes on the offensive against a certain way of life, a culture of chasms and contradictions. Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, Philip Whalen, Gary Snyder, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti proposed a kind of sword lyricism, a hacksaw lyricism, a lyricism totally off the wall, not only revolutionary but beneficial at a time of poetry stagnation—especially in terms of interest for it; an approach meant to pulverize, break canons, be they good or bad, to deny, impose new values, and make us change our concept of aesthetics. These newcomers emphatically assumed both American reality and surreality. The former, through an in-depth knowledge of political trends, relations, issues, slogans, and a very tangible, material mixing in the mud—using an unerring intuition regarding the direction of progress. The latter, through outrageous experience as a means of gaining access to an illusory, uncontrollable, fluctuating, subjective universe. When the ruckus of this newly discovered universe subsided, their experience was claimed by society, graded and recorded: the offbeat authors became instant classics and found some well-deserved global acclaim. Ultimately, the nerve center remained San Francisco, where Lawrence Ferlinghetti bolstered up the “new wave” with a publishing house and a bookstore.

“It also depends on the air,” I said.

“It does indeed. When forgetting to breathe, too little oxygen circulates through the body and that leads to a series of irregularities.”

“The modern man forgets to read poetry,” I added, optimistic then, as I am now, about the function of poetry. But, like air, which so often is unbreathable, does all poetry deserve to be read? Speaking of air, I hear the equatorial forest is being cut down at a speed of a thousand hectares per minute!

As so much lyricism is refreshed periodically through individual—less frequently, collective—efforts, our need is thus kept fresh due to these bouts of renewal fever.

I recalled the discussion in Mexico, meeting Lawrence Ferlinghetti for an interview. I had to go back in my mind to the experience of the Beat Generation, among whose exponents we find Charles Olson and Kenneth Rexroth, though we can’t help but detect the influence, in spirit, of Walt Whitman’s wave of humanity and vitalist frenzy as well as, in letter, the more recent one of Ezra Pound and his zigzag poetics.

Same as animals in danger group together to survive, several young American poets in the ’50s gathered in something like a lyrical pack. The word “pack” implies qualities such as mobility, hunger, action, sharp fangs, grinning, howling—epic feeling. A pack which defends by attacking. It defends poetry—their poetry, from the one that precedes it—and at the same time goes on the offensive against a certain way of life, a culture of chasms and contradictions. Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, Philip Whalen, Gary Snyder, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti proposed a kind of sword lyricism, a hacksaw lyricism, a lyricism totally off the wall, not only revolutionary but beneficial at a time of poetry stagnation—especially in terms of interest for it; an approach meant to pulverize, break canons, be they good or bad, to deny, impose new values, and make us change our concept of aesthetics. These newcomers emphatically assumed both American reality and surreality. The former, through an in-depth knowledge of political trends, relations, issues, slogans, and a very tangible, material mixing in the mud—using an unerring intuition regarding the direction of progress. The latter, through outrageous experience as a means of gaining access to an illusory, uncontrollable, fluctuating, subjective universe. When the ruckus of this newly discovered universe subsided, their experience was claimed by society, graded and recorded: the offbeat authors became instant classics and found some well-deserved global acclaim. Ultimately, the nerve center remained San Francisco, where Lawrence Ferlinghetti bolstered up the “new wave” with a publishing house and a bookstore.

Taken as a group, their poetry appears like a rainbow of rich fabrics thrown diagonally across the US, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The fantastical of the real world lends itself to a reality devoid of any kind of aura, flat and austere. The phantasm, the material, the imprecation, the catchphrase claim their right to verse. A kaleidoscope of virtues and vices! This poetics can be accepted or rejected the same way you come to stop at one or another facet of the kaleidoscope. After so many years, it even better shows the sides that democratized poetry: they brought it back—first, to the market—then to the heart of the people, which is, after all, a big market too, where everything fits together. In the composition of this new kind of lyricism there are also classical and surrealist fragments, a great appetite for deliberation, an unparalleled rhetoric, along with a crazy lust for life, felt through every pore and desired infinitely better, or bettered to infinity. According to Walter Sutton’s American Free Verse: The Modern Revolution in Poetry, the ideational basis consists in “rudiments of eclectic idealism extracted from the teachings of Zen Buddhism and the sacred books of India” and, I would add, in the Baudelaire poetry of the spleen, that “coming across something new,” the blank slate, the unconscious desire for renewal. With anyone against anyone, in defense of poetry: this is the generation in which Ferlinghetti, the author of Open Eye, Open Heart, moves like a mad bishop on the chessboard while Ginsberg jumps in L-shape patterns like a knight. (There is no king, no queen, no rooks, it being a completely democratic chess.)

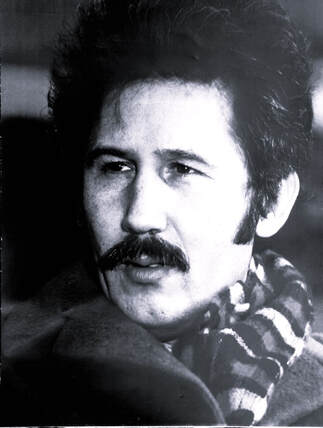

When I met Ginsberg in Genoa, however, he wasn’t the man shrouded in his own beard and hair, pulled out with a straw hook from the cave’s den, who preaches angrily in the town square, squinting at the light. That’s the stereotypical image of the poet. Instead I met a decent, sensible man, attentive and kind to those around him, clean-shaven, wearing a tie. But put him behind a microphone and this shorn lion raises his voice like a mane—and enters a kind of trance. He recites with his voice, with his head, which he moves from side to side, with his hands and feet, accompanied by rhythmic convulsions. The words vibrate not only in the voice, but in his whole body as in a resonance box, amplifying the sound to the maximum. The communication with the audience happens instantly. It’s huge. You can’t tell if he is reciting or shouting or singing—he’s assisted by the sounds of a small accordion, the size of a purse, which he carries around everywhere and which makes an eerie, unsettling noise, of great effect. The poet shakes his head, beats the rhythm with his foot, screams the words out—his poems have an intimate, prophetic character, sparks fly from the accordion-shaped balalaika. Everything has a high impact—whoever hasn’t heard Ginsberg recite may not understand that this poetry is written for this man, this instrument, and this way of reciting. So many shades are lost in the silent reading. A true poet who’s been striving to engage and connect the public with poetry and who has accomplished a lot over the decades, not just thematically, by covering critical and unsophisticated topical issues, but also formally, twinning poetry with song. Statements regarding the attempt to resurrect the oral tradition check out indeed.

The democratization of American poetics in the twentieth century owes a lot to this type of poet, a man of high intelligence and sensitivity, full of emotion, dramatic without dramatizing or, if dramatizing, doing so with art: someone whose deep traumas are overcome in the end, bestowing on the world a wealth of humanism forgotten in our soul, or hidden, of which we are ashamed perhaps, and causing poetry to vibrate as art and way of breathing among the down-and-out from which he rose. He carries with him a bag full of small, primitive instruments utilized by different tribes—for example, some Australian songsticks that, when hammered, give out a dry sound, of beaten wood, and which he uses when singing/reciting Blake’s song-poems. A kind of instrument-man.

When I met Ginsberg in Genoa, however, he wasn’t the man shrouded in his own beard and hair, pulled out with a straw hook from the cave’s den, who preaches angrily in the town square, squinting at the light. That’s the stereotypical image of the poet. Instead I met a decent, sensible man, attentive and kind to those around him, clean-shaven, wearing a tie. But put him behind a microphone and this shorn lion raises his voice like a mane—and enters a kind of trance. He recites with his voice, with his head, which he moves from side to side, with his hands and feet, accompanied by rhythmic convulsions. The words vibrate not only in the voice, but in his whole body as in a resonance box, amplifying the sound to the maximum. The communication with the audience happens instantly. It’s huge. You can’t tell if he is reciting or shouting or singing—he’s assisted by the sounds of a small accordion, the size of a purse, which he carries around everywhere and which makes an eerie, unsettling noise, of great effect. The poet shakes his head, beats the rhythm with his foot, screams the words out—his poems have an intimate, prophetic character, sparks fly from the accordion-shaped balalaika. Everything has a high impact—whoever hasn’t heard Ginsberg recite may not understand that this poetry is written for this man, this instrument, and this way of reciting. So many shades are lost in the silent reading. A true poet who’s been striving to engage and connect the public with poetry and who has accomplished a lot over the decades, not just thematically, by covering critical and unsophisticated topical issues, but also formally, twinning poetry with song. Statements regarding the attempt to resurrect the oral tradition check out indeed.

The democratization of American poetics in the twentieth century owes a lot to this type of poet, a man of high intelligence and sensitivity, full of emotion, dramatic without dramatizing or, if dramatizing, doing so with art: someone whose deep traumas are overcome in the end, bestowing on the world a wealth of humanism forgotten in our soul, or hidden, of which we are ashamed perhaps, and causing poetry to vibrate as art and way of breathing among the down-and-out from which he rose. He carries with him a bag full of small, primitive instruments utilized by different tribes—for example, some Australian songsticks that, when hammered, give out a dry sound, of beaten wood, and which he uses when singing/reciting Blake’s song-poems. A kind of instrument-man.

Allen Ginsberg in 1979

(© Hans van Dijk for Anefo)

Allen Ginsberg in 1979

(© Hans van Dijk for Anefo)

Marin Sorescu: I’ll ask you the same question I asked several poets of today and, I’m hoping, of tomorrow: what do you think about your poetry?

Allen Ginsberg: I’m the apprentice of William Carlos Williams, the modernist, in terms of pursuing the rhythms of everyday speech. I am Ezra Pound’s in the classic quantity of vowels (long and short vowels). I am Master Chögyam Trungpa’s student at the school of Tibetan Buddhism—studying the art of breathing. So, in conclusion: modernist, classicist, Buddhist, hippie, Jew.

MS: One sentence about your last book, please.

AG: It’s called Mind Breaths. The title instantly reveals its focus and content. I spent the last few years exploring the practice of meditation, similar to the Zen school. "Plutonian Ode" is the last poem I wrote.

MS: Is contact with the audience necessary for poetic breathing?

AG: I try to balance my mindset (which has to do with temperament) by practicing contemplation, to be able to develop the peace and calmness to face private, alone solitude, as well as public solitude.

MS: What’s the deal with breathing? Don’t we all breathe the same? I am, I must admit, incognizant of breathing. I breathe as it comes to me. Is it possible otherwise?

AG: I spent a year between 1971 and 1972 in Calcutta and Benares, living in a modest room on the banks of the Ganges. Near the vegetable market and the beggars’ center. It was a five-floor building. Each floor had a large room where a Brahmin lived. Mine was an unfurnished room, $15 a day. I met some really nice Hindu poets but didn’t come across any breathing masters at the time. This is how you breathe: sit with your legs crossed and relax. Breathe. That is, breathe the air in and out and watch how it goes, as if it were cigarette smoke. Like a thin thread breaking apart. And you don’t think about anything. But a thought comes to you. You let it come. You interrupt it when you breathe and go back into deep thought, a particular thought, or a random one, as you exhale through your nose. And you do this for an hour or two. When I’m on holiday I do it up to eight hours a day...

MS: So a day’s work of deep breathing. It must be quite tiring.

AG: Not at all. The same thought comes to you hundreds of times. To the point of boredom. When you get bored, the poetry begins.

MS: When you get bored, the poetry begins. Sounds beautiful, like a verse. Is it yours or mine, because it emerged from the conversation. You said it as prose and I made it verse... (He smiles.)

AG: That’s how all obsessions surface. Political, social, sexual. You filter them and make of them an open universe. You see them as freedoms, joys, rather than obsessions and oppressing thoughts...

MS: Isn’t it a way of cheating yourself? Calling the black white?

AG: It is a means of balancing hectic life, the daily hustle and bustle with the peace within, which exists there but you don’t know it does. A way of ridding yourself of the conscious mind, of repressed emotions and insights, and opening the stream of breathing instead, the life within you which is your breathing.

MS: Do you speak Yiddish?

AG: No. My parents didn’t speak Yiddish. My mother spoke English. She was a communist. My father, less progressive, was a socialist. They argued at home about political issues. That’s how I was inoculated with politics from a young age...

MS: Coming back to the private and public solitude...

AG: They’re one and the same. You must happily accept the vacuum they both create and be in tune with it, as if it were an escape, a release and by no means a problem, a sort of terror. In existential theory, there is vacuum as fear. This void, Sunyata, in Sanskrit also means open—and not a form of claustrophobia. It may sound a bit didactic, but it’s based on practice. On the practice of several days—festivals—and that of every day. Again, it is through breathing one is able to disperse the phantasms and nightmares caused by thinking. This space where we breathe here in the hotel (we are in the lobby of La Plaza Hotel in Genoa) is vacuum itself, but the path from claustrophobia to liberation is wide open.

MS: A final point, which also contributes to the self-definition of your poetry. The most asked question here in Europe is, I believe, why don’t you wear a beard anymore? I noticed some people looking rather disillusioned. They were expecting to see a guy in a costume, something like Yeti the Snowman.

AG: I suffered facial paralysis a few years ago. How did it happen? I was in the hospital for a check-up and they gave me antibiotics, but it turned out the treatment was contraindicated. I was allergic to antibiotics. I remained hospitalized a whole month. After that I was cured by a Chinese doctor, with acupuncture. In order to see where to stick the needles, he made me shave and then I stayed shaven. Does it harm poetry in any way?

MS: I think not.

AG: I was left with a small rictus and sometimes one of my eyes tears up out of the blue. I can’t control my eye sometimes. As you can see, I discovered weeping without pain.

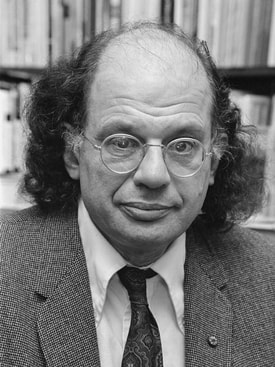

The sincerity with which Ginsberg speaks and confesses is disarming, as is his poetry. Like him, Ferlinghetti had to first win over the poetry reader to be accepted. His poems, written “with one eye on the world,” an eye like a suction cup, dismayed the critics. There was talk of non-poetry, non-lyricism, and other nons, largely absurd inventions from which a big yes resulted in the end, the final seal of any authentic creation—no matter how many obstacles it faces. The role of some critics is to be the benchmark for misunderstanding the real and truly innovative poetry of their time.

Allen Ginsberg: I’m the apprentice of William Carlos Williams, the modernist, in terms of pursuing the rhythms of everyday speech. I am Ezra Pound’s in the classic quantity of vowels (long and short vowels). I am Master Chögyam Trungpa’s student at the school of Tibetan Buddhism—studying the art of breathing. So, in conclusion: modernist, classicist, Buddhist, hippie, Jew.

MS: One sentence about your last book, please.

AG: It’s called Mind Breaths. The title instantly reveals its focus and content. I spent the last few years exploring the practice of meditation, similar to the Zen school. "Plutonian Ode" is the last poem I wrote.

MS: Is contact with the audience necessary for poetic breathing?

AG: I try to balance my mindset (which has to do with temperament) by practicing contemplation, to be able to develop the peace and calmness to face private, alone solitude, as well as public solitude.

MS: What’s the deal with breathing? Don’t we all breathe the same? I am, I must admit, incognizant of breathing. I breathe as it comes to me. Is it possible otherwise?

AG: I spent a year between 1971 and 1972 in Calcutta and Benares, living in a modest room on the banks of the Ganges. Near the vegetable market and the beggars’ center. It was a five-floor building. Each floor had a large room where a Brahmin lived. Mine was an unfurnished room, $15 a day. I met some really nice Hindu poets but didn’t come across any breathing masters at the time. This is how you breathe: sit with your legs crossed and relax. Breathe. That is, breathe the air in and out and watch how it goes, as if it were cigarette smoke. Like a thin thread breaking apart. And you don’t think about anything. But a thought comes to you. You let it come. You interrupt it when you breathe and go back into deep thought, a particular thought, or a random one, as you exhale through your nose. And you do this for an hour or two. When I’m on holiday I do it up to eight hours a day...

MS: So a day’s work of deep breathing. It must be quite tiring.

AG: Not at all. The same thought comes to you hundreds of times. To the point of boredom. When you get bored, the poetry begins.

MS: When you get bored, the poetry begins. Sounds beautiful, like a verse. Is it yours or mine, because it emerged from the conversation. You said it as prose and I made it verse... (He smiles.)

AG: That’s how all obsessions surface. Political, social, sexual. You filter them and make of them an open universe. You see them as freedoms, joys, rather than obsessions and oppressing thoughts...

MS: Isn’t it a way of cheating yourself? Calling the black white?

AG: It is a means of balancing hectic life, the daily hustle and bustle with the peace within, which exists there but you don’t know it does. A way of ridding yourself of the conscious mind, of repressed emotions and insights, and opening the stream of breathing instead, the life within you which is your breathing.

MS: Do you speak Yiddish?

AG: No. My parents didn’t speak Yiddish. My mother spoke English. She was a communist. My father, less progressive, was a socialist. They argued at home about political issues. That’s how I was inoculated with politics from a young age...

MS: Coming back to the private and public solitude...

AG: They’re one and the same. You must happily accept the vacuum they both create and be in tune with it, as if it were an escape, a release and by no means a problem, a sort of terror. In existential theory, there is vacuum as fear. This void, Sunyata, in Sanskrit also means open—and not a form of claustrophobia. It may sound a bit didactic, but it’s based on practice. On the practice of several days—festivals—and that of every day. Again, it is through breathing one is able to disperse the phantasms and nightmares caused by thinking. This space where we breathe here in the hotel (we are in the lobby of La Plaza Hotel in Genoa) is vacuum itself, but the path from claustrophobia to liberation is wide open.

MS: A final point, which also contributes to the self-definition of your poetry. The most asked question here in Europe is, I believe, why don’t you wear a beard anymore? I noticed some people looking rather disillusioned. They were expecting to see a guy in a costume, something like Yeti the Snowman.

AG: I suffered facial paralysis a few years ago. How did it happen? I was in the hospital for a check-up and they gave me antibiotics, but it turned out the treatment was contraindicated. I was allergic to antibiotics. I remained hospitalized a whole month. After that I was cured by a Chinese doctor, with acupuncture. In order to see where to stick the needles, he made me shave and then I stayed shaven. Does it harm poetry in any way?

MS: I think not.

AG: I was left with a small rictus and sometimes one of my eyes tears up out of the blue. I can’t control my eye sometimes. As you can see, I discovered weeping without pain.

The sincerity with which Ginsberg speaks and confesses is disarming, as is his poetry. Like him, Ferlinghetti had to first win over the poetry reader to be accepted. His poems, written “with one eye on the world,” an eye like a suction cup, dismayed the critics. There was talk of non-poetry, non-lyricism, and other nons, largely absurd inventions from which a big yes resulted in the end, the final seal of any authentic creation—no matter how many obstacles it faces. The role of some critics is to be the benchmark for misunderstanding the real and truly innovative poetry of their time.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti (© Elsa Dorfman, via Wikimedia Commons)

Lawrence Ferlinghetti (© Elsa Dorfman, via Wikimedia Commons)

Ferlinghetti was born in New York, studied at Columbia University, and received a PhD from the Sorbonne. He founded City Lights Books and the Journal for the Protection of All Beings. Tall, strong, bearded, he doesn't betray his age. Our discussion takes place in the lobby of the Montejo Hotel in Mexico City, not far from the huge statue of the Angel of Independence, El Ángel, which dominates the boulevard Paseo de la Reforma, designed by Emperor Maximilian as a replica to the Champs Elysées. So right in the center of a cyclopean city, where millions of cars are running continuously, honking and spraying with smoke the palm trees that try to rise higher and higher in order to breathe. Our hotel, built in an elegant colonial style, is a peaceful oasis. The schedule of a poetry festival is always packed full of visits to art galleries, tourist attractions, receptions, in addition to the poetry sessions themselves. We normally leave a couple of hours early to get to the theater on time and still manage to keep the spectators waiting. At the moment, while having this chat, the hotel lobby seems to be, so to speak, oversaturated with poetry and poets. The Swedish academician Lars Forssell is looking out onto the street. He arrived a little irritated, less than his usual calm, collected self. Two hours after takeoff his plane suffered an engine failure and was forced to return to Stockholm and wait for another aircraft. The English poet Ted Hughes keeps checking the clock. He is not very communicative either (when he reads his long, narrative poems, he has his eyes fixed on his papers and never looks at the room. It was a great pain for the photographers to capture his gaze, so essential to a good picture). The Brazilian poet and prose writer Ivo Lêdo, short, lively, mercurial, curious to know everything, exchanges impressions with Charles Tomlinson from their trip to Teotihuacan. Both wonderful people. Tomlinson writes down everything in a notebook, perhaps a diary, given that the main quality of memory is forgetting... Who said that? I forgot. Good friends with Octavio Paz, they wrote a volume of poems together, through correspondence. Paz a line, Tomlinson a line. Sonnets, evidently. A few days ago, at the opening gala, he read one of his own, in response to a sonnet written by Paz.

The minibus that will be taking us to the edge of this endless city is stuck in traffic, so we make the most of it.

Marin Sorescu: You were invited to the World Poetry Congress in Madrid. I was expecting to see you there.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti: Yes, I would have liked to come, but it coincided with the anniversary of our generation. Twenty-five years since the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. The meeting was in Colorado.

MS: Were you all there?

LF: Everyone who’s still alive, yes. (He smiles.) And... the spirits of those who are no more.

MS: Tell me something about your poetry. Anything. I don’t do standard interviews.

LF: Perhaps you should consider using a tape recorder.

MS: I don’t have one. But it doesn’t matter, I prefer to make notes. I find technology an excuse for being lazy. Also, it inhibits me.

LF: Ever since I was a child, the world appeared to me to be something amazing, exciting, and absurd at the same time. When I was five it seemed everywhere I looked there was a brightly lit screen behind things. As if the world were a stage lit from the back. Everything continued to be strange, absurd for me even at the age of ten. Later I realized that this absurdity was not necessarily in the spirit of Kafka and Beckett, but rather a hilarious absurdity, which included irony, satire. The bookstore I have in San Francisco is called “City Lights”, the title of a Chaplin film. I picked the name because Chaplin’s universe was perhaps the closest to my own.

MS: Why did you start writing poetry? Why didn’t you start with painting, which may be said to represent your main area of interest now?

LF: All the experiences I was just recounting simply pushed me towards poetry. It’s not my fault. I’ve been writing since I was seven years old.

MS: Are there any other writers in your family?

LF: My grandfather. He was of Portuguese origin, Sephardic, a language teacher in the Caribbean. My family had lived there since the twelfth century. He was a polyglot, with a truly exceptional talent for languages, by the name of Mendes Monsanto. He emigrated to New York as a teacher. Another ancestor of mine, on my mother’s side, who painted instead of writing, was Camille Pissaro, also Sephardic, born in the Virgin Islands. But my father was Italian. He died before I was born.

MS: So you are Italian, Portuguese, Sephardic, American. What was your first great poetic success?

LF: The book I gave you (A Coney Island of the Mind). It has been printed so far in one million copies. The usual print run in the United States is 1,000 copies and it takes a few years for the books to sell out.

The minibus that will be taking us to the edge of this endless city is stuck in traffic, so we make the most of it.

Marin Sorescu: You were invited to the World Poetry Congress in Madrid. I was expecting to see you there.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti: Yes, I would have liked to come, but it coincided with the anniversary of our generation. Twenty-five years since the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. The meeting was in Colorado.

MS: Were you all there?

LF: Everyone who’s still alive, yes. (He smiles.) And... the spirits of those who are no more.

MS: Tell me something about your poetry. Anything. I don’t do standard interviews.

LF: Perhaps you should consider using a tape recorder.

MS: I don’t have one. But it doesn’t matter, I prefer to make notes. I find technology an excuse for being lazy. Also, it inhibits me.

LF: Ever since I was a child, the world appeared to me to be something amazing, exciting, and absurd at the same time. When I was five it seemed everywhere I looked there was a brightly lit screen behind things. As if the world were a stage lit from the back. Everything continued to be strange, absurd for me even at the age of ten. Later I realized that this absurdity was not necessarily in the spirit of Kafka and Beckett, but rather a hilarious absurdity, which included irony, satire. The bookstore I have in San Francisco is called “City Lights”, the title of a Chaplin film. I picked the name because Chaplin’s universe was perhaps the closest to my own.

MS: Why did you start writing poetry? Why didn’t you start with painting, which may be said to represent your main area of interest now?

LF: All the experiences I was just recounting simply pushed me towards poetry. It’s not my fault. I’ve been writing since I was seven years old.

MS: Are there any other writers in your family?

LF: My grandfather. He was of Portuguese origin, Sephardic, a language teacher in the Caribbean. My family had lived there since the twelfth century. He was a polyglot, with a truly exceptional talent for languages, by the name of Mendes Monsanto. He emigrated to New York as a teacher. Another ancestor of mine, on my mother’s side, who painted instead of writing, was Camille Pissaro, also Sephardic, born in the Virgin Islands. But my father was Italian. He died before I was born.

MS: So you are Italian, Portuguese, Sephardic, American. What was your first great poetic success?

LF: The book I gave you (A Coney Island of the Mind). It has been printed so far in one million copies. The usual print run in the United States is 1,000 copies and it takes a few years for the books to sell out.

MS: If you were a literary critic, how would you describe your own poetry?

LF: A living poem, written for the people on the street, for everyday people.

MS: A poem particularly made to be heard by the people on the street because, as I noticed yesterday in the university hall, you have a special way of reciting your poems. There is a common feature—even in the way of reading—in all beatniks. Ginsberg, whom I’ve had the privilege of hearing more often—I would call him the one-man-orchestra poet—also uses a small accordion. You seem to be able to achieve good effects only from intonation and a remarkable diction. The audience was thrilled. But I interrupted you.

LF: And I would add: an American poem, in the tradition of Kenneth Rexroth and Kenneth Patchen. Very engaged, visual poetics. Each of my poems is a complete painting. Besides, visual perception constitutes the essential factor of my inspiration. Last night you listened to the poem “Away Above a Harborful”. If you noticed, there was a complete image there. An enthralling sight, like a photograph.

MS: Yes, it’s true that detail shocks in your poetry, whether or not it becomes significant. The whole cascading of it really tends to catch the eye, impress, I would say, by using the same means as painting or artistic photography.

LF: The concrete is the most poetic. Small details make big poetry. And then, there obviously comes a point when you go beyond the concrete.

MS: When the concrete becomes symbol.

LF: Critics didn’t really approve of me; I’m too popular to be endorsed. They still see poetry through snob glasses. What the public likes is not poetry. I suffer from being too clear.

MS: What type of function do you assign to verse fragmentation, as it appears in your writing?

LF: Verse fragmentation is necessary to show how the poem should be read. How words should be stressed.

MS: Do you have imitators?

LF: Many tried, then gave up. Everyone has their own sensibility, which can only be imitated superficially. You can smell imitation from a mile away. Only the naive and truly stupid think they can become great by imitating one way of writing or another. It’s fine to learn of course, to read all poets as carefully as possible and respect those from whom you learn the most.

MS: Usually the exact opposite happens. Some pretend they’ve never heard of those from whom they’ve taken something.

LF: For instance, Lars Forssell’s sensibility is difficult to imitate, because it is his alone, an entirely particular sensibility. The same goes for all great poets. Besides, that’s what every great artist does. He sees what others do not... Like the poems I heard you read last night. They are different from everything I know about poetry. They are poems that enrich you.

MS: I know you’re in love with San Francisco. I’ve also been there many times, a wonderful city. One of the most beautiful I have ever seen. I even visited the “City Lights” bookstore last year, but didn’t have the good fortune of running into you.

LF: San Francisco has a special charm indeed. It’s a little European, a little Mediterranean. My bookstore, as you saw, is uptown, next to Chinatown. But I live by the docks. I like the sea. I was a sailor for five years. See, I walk around in a sailor cap, I feel like a sailor and need to live by the sea. I couldn’t possibly live in the mountains.

MS: How do you share your time between poetry and painting?

LF: These days I spend most of my free time as a painter, so to speak.

MS: What kind of paintings do you do?

LF: Expressionist, symbolist. They’re becoming more and more sought after in San Francisco. I will be putting on an exhibition there next month. Also, the bookstore takes up a lot of my time.

MS: Which actually is a publishing house.

LF: Yes, we publish books. Ginsberg’s new ones, too.

MS: Do you enjoy traveling?

LF: Yes, but not like before. When I was younger, I hitchhiked all over Mexico. And France. And many other countries. Always by myself. But now I seem to get bored being on my own. The more the merrier.

MS: Skeptics say you aren’t actually a beatnik because of a deficit of vices. Is it true?

LF: (He smiles.) I feel closely connected to this generation.

MS: Speaking of which, there is a strong connection between your poetry and jazz. Do you like jazz?

LF: I love jazz. But, as I said, I’m more of a visual person.

MS: Tell me again that you like the sea. The sea rhymes so well with the poetry you write. I want to thank you for the answers and for the million-copy book you gave me. I reserve myself the pleasure of reading it on the plane, to be one out of the million, in any case the one reading it at such high altitude, over such a great ocean.

LF: A living poem, written for the people on the street, for everyday people.

MS: A poem particularly made to be heard by the people on the street because, as I noticed yesterday in the university hall, you have a special way of reciting your poems. There is a common feature—even in the way of reading—in all beatniks. Ginsberg, whom I’ve had the privilege of hearing more often—I would call him the one-man-orchestra poet—also uses a small accordion. You seem to be able to achieve good effects only from intonation and a remarkable diction. The audience was thrilled. But I interrupted you.

LF: And I would add: an American poem, in the tradition of Kenneth Rexroth and Kenneth Patchen. Very engaged, visual poetics. Each of my poems is a complete painting. Besides, visual perception constitutes the essential factor of my inspiration. Last night you listened to the poem “Away Above a Harborful”. If you noticed, there was a complete image there. An enthralling sight, like a photograph.

MS: Yes, it’s true that detail shocks in your poetry, whether or not it becomes significant. The whole cascading of it really tends to catch the eye, impress, I would say, by using the same means as painting or artistic photography.

LF: The concrete is the most poetic. Small details make big poetry. And then, there obviously comes a point when you go beyond the concrete.

MS: When the concrete becomes symbol.

LF: Critics didn’t really approve of me; I’m too popular to be endorsed. They still see poetry through snob glasses. What the public likes is not poetry. I suffer from being too clear.

MS: What type of function do you assign to verse fragmentation, as it appears in your writing?

LF: Verse fragmentation is necessary to show how the poem should be read. How words should be stressed.

MS: Do you have imitators?

LF: Many tried, then gave up. Everyone has their own sensibility, which can only be imitated superficially. You can smell imitation from a mile away. Only the naive and truly stupid think they can become great by imitating one way of writing or another. It’s fine to learn of course, to read all poets as carefully as possible and respect those from whom you learn the most.

MS: Usually the exact opposite happens. Some pretend they’ve never heard of those from whom they’ve taken something.

LF: For instance, Lars Forssell’s sensibility is difficult to imitate, because it is his alone, an entirely particular sensibility. The same goes for all great poets. Besides, that’s what every great artist does. He sees what others do not... Like the poems I heard you read last night. They are different from everything I know about poetry. They are poems that enrich you.

MS: I know you’re in love with San Francisco. I’ve also been there many times, a wonderful city. One of the most beautiful I have ever seen. I even visited the “City Lights” bookstore last year, but didn’t have the good fortune of running into you.

LF: San Francisco has a special charm indeed. It’s a little European, a little Mediterranean. My bookstore, as you saw, is uptown, next to Chinatown. But I live by the docks. I like the sea. I was a sailor for five years. See, I walk around in a sailor cap, I feel like a sailor and need to live by the sea. I couldn’t possibly live in the mountains.

MS: How do you share your time between poetry and painting?

LF: These days I spend most of my free time as a painter, so to speak.

MS: What kind of paintings do you do?

LF: Expressionist, symbolist. They’re becoming more and more sought after in San Francisco. I will be putting on an exhibition there next month. Also, the bookstore takes up a lot of my time.

MS: Which actually is a publishing house.

LF: Yes, we publish books. Ginsberg’s new ones, too.

MS: Do you enjoy traveling?

LF: Yes, but not like before. When I was younger, I hitchhiked all over Mexico. And France. And many other countries. Always by myself. But now I seem to get bored being on my own. The more the merrier.

MS: Skeptics say you aren’t actually a beatnik because of a deficit of vices. Is it true?

LF: (He smiles.) I feel closely connected to this generation.

MS: Speaking of which, there is a strong connection between your poetry and jazz. Do you like jazz?

LF: I love jazz. But, as I said, I’m more of a visual person.

MS: Tell me again that you like the sea. The sea rhymes so well with the poetry you write. I want to thank you for the answers and for the million-copy book you gave me. I reserve myself the pleasure of reading it on the plane, to be one out of the million, in any case the one reading it at such high altitude, over such a great ocean.

|

Interview available for the first time in English (translation © Daniel Nemo) by kind permission of the Marin Sorescu Foundation. Original text first published in Tratat de Inspirație by Marin Sorescu (Scrisul Românesc, 1985).

|

|

Daniel Nemo is a poet, translator, and photographer. His work is forthcoming or has appeared in RHINO, Full Stop, Dream Catcher, Brazos River Review, Off the Coast, Pennsylvania Literary Journal, and elsewhere. More info at www.danielnemo.com

|