Diana Khoi Nguyen talks to Daniel Nemo about art as a reaching toward and beyond, trusting the unconscious, and making the absent present. |

Daniel Nemo: I’d like to start by asking about your development as a poet and a visual artist. Because it appears the two blend together seamlessly, effortlessly even, in your work.

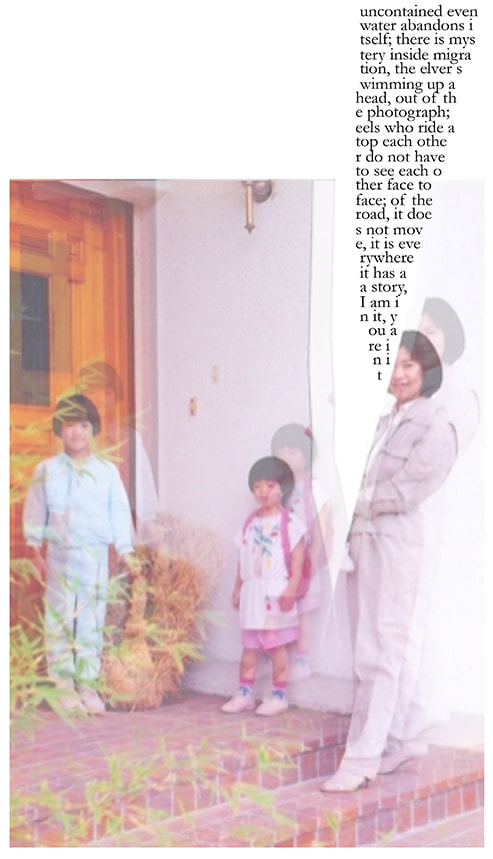

Diana Khoi Nguyen: I always feel a little sheepish about the term artist or visual artist because my training is primarily as a poet. My work with images is due to chance, since it was initially occasioned by the image artifacts related to my brother's suicide. An unfortunately way to begin visual work, but the nature of the personal events felt necessary for me. And since I think primarily as a poet, my way of engagement is through language and text—in the case of working with my family's photographs (and later, home videos), I sought to compose in spaces in the photograph, to treat moving and still image as a kind of text (because they are). Each year I return to the same family archives, incorporating new artifacts and different approaches to seeing, holding, and making. It's very much a ritual and an obsession, too—since I make/write around the anniversary of my brother's death.

DN: What does your work process consist of?

DKN: Chiefly in two intensive writing and making periods: about 15 days in the summer and 15 days in December, around my brother's death anniversary. The goal is usually as polished a piece as possible for each of these days (which results in very concentrated and pressurized days), and the rest of the year is dedicated to foraging, brainstorming, wondering/wandering, being present in the world like a sponge, reading widely across disciplines and genres, taking in art and life, being present, curious, and alive. A small portion of the year (maybe just about a week) is spent looking back at what I've generated to see if it coalesces, if it might find a home in a journal, and so forth. There's not too much revision in a transitional sense—I revise during my intensive writing, editing as I'm composing, and not so much after the fact. For me, rewriting anew is my form of revision.

DN: Some of your poems, beautiful in their spareness, seem to be carved out of longer pieces. One gets a sense that you pare those down until they become compatible with some inexpressible reality. Is that the way the work sometimes comes to life?

DKN: Yes, it is! Thank you for that attuned observation—sometimes I'm not sure what's contained in my mind, and I allow myself freedom to put anything/everything down on the page. And as I lay things out, I am also editing/contracting the material as I go—or in some rare instances, a ten-page poem might become just a few lines (as in the case of the first poem in Ghost Of). More recently, my work has become quite serial due to my intensive writing periods. This is less a paring down, but the writing process is like this: laying down a sentence, pushing the sentence to its emotional and syntactical limits (which is arbitrary, perhaps), then revising that sentence in myriad ways before laying down the next sentence. And so forth. Sometimes it's like what I imagine bricklaying might feel like—or the traditional craft of assembling a stone wall.

DN: Do you see your work as separate entities or one long epic poem? If so, can a unity, like Tsvetaeva says, really give a sum?

DKN: You know, I see it as both! More like a constellation of celestial bodies or stars—each one is their own entity, but they accumulate into a larger image/concept--

DN: It seems to me telling and showing in your poems—and particularly in Ghost Of—conjures up, paradoxically, a point of application in effacement, like Eliot’s “still point of the turning world,” neither from nor towards, neither here nor there. Erasure and silence become an intrinsic part of communication, articulating vacuums and lapses. Is the resulting tension the main emphasis of the collection?

DKN: What a remarkable way of seeing the poems, thank you so much for sharing this with me. Yes, there is very much a tension between presence and absence, sound and silence—which stems from the brother's erasure in life and the archive. In working with the archive and composition, I wasn't thinking about this tension at all, but mainly circling the wound of the void, the erasure, documenting how I felt, what I remember, recall—the flawed faculty of memory.

DN: I’ve personally come to realize that grief is not a linear experience. It’s not something you can work through in time and which eventually dwindles or goes away. How do you see it? What is your relationship to it?

DKN: Absolutely I see grief as a nonlinear experience; it is one of recursion, and it has its own rules of physics that I am still learning and subject to. In the early days of grief, it felt very much as though I were on a foreign planet, trying to figure out how to stay alive according to the unknown laws of that planet's physics. Eventually, I acclimated, felt less fear and despair, and over the years, I came to view the terrain as familiar. It's like being an immigrant on the planet of grief. And eventually, I will have lived on this new planet for longer than I lived on my home planet.

DN: How much of Ghost Of came by itself, one might say as natural outcome of unconscious activity, and how much as conscious preoccupation with the theme?

DKN: Oh it's nearly all unconscious activity, as once I think actively about a "theme," I feel a kind of stage fright, or even trapped in a way. I trust in my imagination at all times even if I have no idea what is coming out, what is going on, what is being made. Only after accumulating a larger body of pieces do I dare take a look at the "whole" to see what's there—and is there something there? It's very intuitive, and involves a lot of trust in my brain's mysterious workings. Though I feel uncertain throughout the process; it's an unending existential crisis nearly all the time, too.

DN: Art has the power to impede existential solitude. The closeness and connection a reader can feel to a long-dead artist through their work can often be unparalleled to any other member of the living. Has your work sometimes reoriented you across time and space, transcended them perhaps—as well as the realm of the unliving? More exactly, do you believe it could be something of a two-way exchange, a type of reflective radiance, rather than a one-way passage?

DKN: Ooh I love this reflection and question! Yes, it's definitely a two-way exchange, and I'm constantly pondering how to translate the nonverbal forms of communing/communication that I encounter. Perhaps the first step is acknowledging and welcoming this nonverbal material into the process and journey, to recognize that it exists. Sometimes, I think about how particles "communicate" at the edge of a black hole—I'm terrible at science, so I won't try to explain it here, but it involves deduction, proximity, and things happening at levels invisible to the naked human eye. In writing some of the poems in the book, I was very much speaking aloud and reaching toward my deceased brother.

DN: Paul Celan said there is only one thing that remains within reach amid all losses—language. Do you think poetry can act as a vehicle of salvation?

DKN: I'm not sure about salvation for all things, but I do think that poetry (verbal and nonverbal) can serve as a temporary salve. That it aids me in my journey toward more compassion, understanding, and peace with being alive, with having survived various aspects of the past.

Diana Khoi Nguyen: I always feel a little sheepish about the term artist or visual artist because my training is primarily as a poet. My work with images is due to chance, since it was initially occasioned by the image artifacts related to my brother's suicide. An unfortunately way to begin visual work, but the nature of the personal events felt necessary for me. And since I think primarily as a poet, my way of engagement is through language and text—in the case of working with my family's photographs (and later, home videos), I sought to compose in spaces in the photograph, to treat moving and still image as a kind of text (because they are). Each year I return to the same family archives, incorporating new artifacts and different approaches to seeing, holding, and making. It's very much a ritual and an obsession, too—since I make/write around the anniversary of my brother's death.

DN: What does your work process consist of?

DKN: Chiefly in two intensive writing and making periods: about 15 days in the summer and 15 days in December, around my brother's death anniversary. The goal is usually as polished a piece as possible for each of these days (which results in very concentrated and pressurized days), and the rest of the year is dedicated to foraging, brainstorming, wondering/wandering, being present in the world like a sponge, reading widely across disciplines and genres, taking in art and life, being present, curious, and alive. A small portion of the year (maybe just about a week) is spent looking back at what I've generated to see if it coalesces, if it might find a home in a journal, and so forth. There's not too much revision in a transitional sense—I revise during my intensive writing, editing as I'm composing, and not so much after the fact. For me, rewriting anew is my form of revision.

DN: Some of your poems, beautiful in their spareness, seem to be carved out of longer pieces. One gets a sense that you pare those down until they become compatible with some inexpressible reality. Is that the way the work sometimes comes to life?

DKN: Yes, it is! Thank you for that attuned observation—sometimes I'm not sure what's contained in my mind, and I allow myself freedom to put anything/everything down on the page. And as I lay things out, I am also editing/contracting the material as I go—or in some rare instances, a ten-page poem might become just a few lines (as in the case of the first poem in Ghost Of). More recently, my work has become quite serial due to my intensive writing periods. This is less a paring down, but the writing process is like this: laying down a sentence, pushing the sentence to its emotional and syntactical limits (which is arbitrary, perhaps), then revising that sentence in myriad ways before laying down the next sentence. And so forth. Sometimes it's like what I imagine bricklaying might feel like—or the traditional craft of assembling a stone wall.

DN: Do you see your work as separate entities or one long epic poem? If so, can a unity, like Tsvetaeva says, really give a sum?

DKN: You know, I see it as both! More like a constellation of celestial bodies or stars—each one is their own entity, but they accumulate into a larger image/concept--

DN: It seems to me telling and showing in your poems—and particularly in Ghost Of—conjures up, paradoxically, a point of application in effacement, like Eliot’s “still point of the turning world,” neither from nor towards, neither here nor there. Erasure and silence become an intrinsic part of communication, articulating vacuums and lapses. Is the resulting tension the main emphasis of the collection?

DKN: What a remarkable way of seeing the poems, thank you so much for sharing this with me. Yes, there is very much a tension between presence and absence, sound and silence—which stems from the brother's erasure in life and the archive. In working with the archive and composition, I wasn't thinking about this tension at all, but mainly circling the wound of the void, the erasure, documenting how I felt, what I remember, recall—the flawed faculty of memory.

DN: I’ve personally come to realize that grief is not a linear experience. It’s not something you can work through in time and which eventually dwindles or goes away. How do you see it? What is your relationship to it?

DKN: Absolutely I see grief as a nonlinear experience; it is one of recursion, and it has its own rules of physics that I am still learning and subject to. In the early days of grief, it felt very much as though I were on a foreign planet, trying to figure out how to stay alive according to the unknown laws of that planet's physics. Eventually, I acclimated, felt less fear and despair, and over the years, I came to view the terrain as familiar. It's like being an immigrant on the planet of grief. And eventually, I will have lived on this new planet for longer than I lived on my home planet.

DN: How much of Ghost Of came by itself, one might say as natural outcome of unconscious activity, and how much as conscious preoccupation with the theme?

DKN: Oh it's nearly all unconscious activity, as once I think actively about a "theme," I feel a kind of stage fright, or even trapped in a way. I trust in my imagination at all times even if I have no idea what is coming out, what is going on, what is being made. Only after accumulating a larger body of pieces do I dare take a look at the "whole" to see what's there—and is there something there? It's very intuitive, and involves a lot of trust in my brain's mysterious workings. Though I feel uncertain throughout the process; it's an unending existential crisis nearly all the time, too.

DN: Art has the power to impede existential solitude. The closeness and connection a reader can feel to a long-dead artist through their work can often be unparalleled to any other member of the living. Has your work sometimes reoriented you across time and space, transcended them perhaps—as well as the realm of the unliving? More exactly, do you believe it could be something of a two-way exchange, a type of reflective radiance, rather than a one-way passage?

DKN: Ooh I love this reflection and question! Yes, it's definitely a two-way exchange, and I'm constantly pondering how to translate the nonverbal forms of communing/communication that I encounter. Perhaps the first step is acknowledging and welcoming this nonverbal material into the process and journey, to recognize that it exists. Sometimes, I think about how particles "communicate" at the edge of a black hole—I'm terrible at science, so I won't try to explain it here, but it involves deduction, proximity, and things happening at levels invisible to the naked human eye. In writing some of the poems in the book, I was very much speaking aloud and reaching toward my deceased brother.

DN: Paul Celan said there is only one thing that remains within reach amid all losses—language. Do you think poetry can act as a vehicle of salvation?

DKN: I'm not sure about salvation for all things, but I do think that poetry (verbal and nonverbal) can serve as a temporary salve. That it aids me in my journey toward more compassion, understanding, and peace with being alive, with having survived various aspects of the past.

"Gyotaku", "Triptych", "Ghost Of"

by Diana Khoi Nguyen

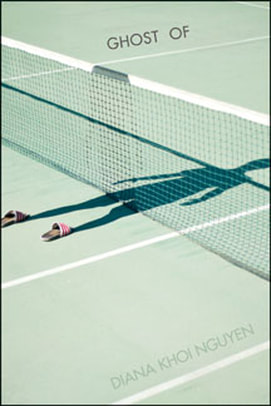

Ghost Of

|

|

A poet and multimedia artist, Diana Khoi Nguyen is the author of Ghost Of (Omnidawn 2018) and recipient of a 2021 fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. In addition to winning the 92Y Discovery Poetry Contest, 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and Colorado Book Award, she was also a finalist for the National Book Award and L.A. Times Book Prize. A Kundiman fellow, she is core faculty in the Randolph College Low-Residency MFA and an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh. In Spring 2022, she was an artist-in-residence at Brown University.

|