Marrakesh, October 1984

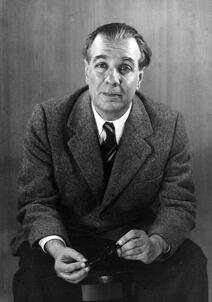

A man guided by a seemingly enchanted cane, for it appears he’s also been able to see with it for a while. The cane has so far contemplated and recounted to him half of the globe. What am I saying: three quarters, five quarters, because it has also explored its celestial halo! Tall and straight as an arrow at eighty-four, always dressed as if about to join a grand ceremony, Borges travels. The world—if not exactly a reception—is a spectacle. Open a door and you step right into a miracle; take a turn on a road or continent and you’re someone else. So he, eternal seeker of everlasting youth, keeps coming and going through the valley of shadows exhausting the fantastic and stunning reality. Especially the trodden, hard-to-reach paths followed in joyful moments by magicians, prophets, poets, philosophers, strangely guide him along. The elaborate attire is nothing but a trap—a way to neutralize himself and gain entry to the most implausible of worlds as ambassador of reason and inquisitive spirit, accredited with mysteries and the fundamental laws of magic. In his travels, his being soaks up as much of the tangible as possible: landscape, events, shapes, faces. Sheets of reality that enwrap him, producing, upon touch, a kind of ecstasy of the senses. I’ve seen his face light up like a child’s many times. He must be a sad man, although something like a happiness floats around him, a kind of bright halo which his miraculous thinking assembles for him daily, and which keeps him company.

“Isn’t that Borges?” I ask my friends at the table.

"Sure. He arrived from Italy this morning."

He’s with Maria Kodama, such a warm and natural presence. They sit somewhat isolated, at the back of the room. Guest of honor at all the major poetry festivals, his name on the participants list seems more like a fantasy of the organizers, or a subterfuge to attract other personalities. And when Borges suddenly appears, the poets rub their eyes in disbelief.

“Isn’t that Borges?” I ask my friends at the table.

"Sure. He arrived from Italy this morning."

He’s with Maria Kodama, such a warm and natural presence. They sit somewhat isolated, at the back of the room. Guest of honor at all the major poetry festivals, his name on the participants list seems more like a fantasy of the organizers, or a subterfuge to attract other personalities. And when Borges suddenly appears, the poets rub their eyes in disbelief.

Marin Sorescu: How did you sleep, Mr. Borges? Does one sleep well in Africa?

He raises his clear eyes and looks at me, as if really seeing me. It's morning. Marrakesh sends a yellowish Sahara light into the hotel room—the sunrise multiplied on sand crystals and filtered through very tall palm trees that come all the way up to the window.

Jorge Luis Borges: I dreamed I was in a hotel in Buenos Aires, in the southern part of the city. And when I woke I heard the muezzin. Do you know what it says?

MS: "There is only one God and Muhammad is his prophet."

JLB: Yes, that's what I heard. And I realized I’m not in Buenos Aires. One sleeps well in Africa... There’s a wildlife park somewhere around here... I fell asleep thinking I’d hear roars...

MS: Of blue tigers? Of the enchanted stones of the High Atlas Mountains? How do you like this morning? Do you like mornings?

JLB: Yes, because they give the illusion of a beginning. They make you think something begins again. But that is false.

MS: And yet we enjoy being deceived this way...

JLB: Indeed, there is complicity in this illusion. After I have my coffee, however, I feel fine.

MS: I believe the interview is a strange animal and it could possibly make an appearance in your book of fantastic animals. A kind of Bahamut, made out of two different breaths, half visible and half invisible. Resting on an answer and carrying a question on its back. I’d like our animal to be more answer though. The fatality of always being asked about your writing will function this time too. Do you accept it?

JLB: Yes.

MS: I didn't prepare any questions. When we were going down to the conference room yesterday, I heard you counting the steps out loud. There were several series of stairs, like in your stories. You were counting each flight in a different language. You were descending as if down a mystery you had visited before. I thought then to ask you about labyrinths—figured the obsession with labyrinths would be a good question for Borges. Besides, everyone asks it.

JLB: I’ve just been to Crete. They made me doctor honoris causa. Instead of helping me understand the Cretan labyrinth better, they made me doctor honoris causa in it. In the labyrinth. (He laughs.) This labyrinth obsession is old. Because I’ve always felt lost. And this loss is the labyrinth…

MS: Maybe that's why you travel so much... To find yourself in the world... Has anyone made a map of your travels?

JLB: No.

MS: You are fascinated by the root of things, the root of words. The labyrinth is perhaps the root of a stone tree. That's why you feel enticed by it, because it’s a root.

JLB: The word "labyrinth" is a triumph in itself. An ingenious word. I want to write a poem about Theseus. The labyrinth is always there and we are in the labyrinth. It was built by someone. The labyrinth is a center and one feels lost—as I always do—at the center. But the universe is not a labyrinth. It's chaos. Day, night, the four seasons— they all make us believe that everything that surrounds us isn’t chaos, that there is a secret cosmos. And that we could find Ariadne’s thread.

MS: Is it possible?

JLB: I don't know. We have to look for it. Someone said finding a solution is not that important. It is important to search. To search forever. To search, always, even without hope. Poetry is an attempt at orientation—in the world—like science is. When we talk about technology, and this happens all the time, we talk about it as if it was something overwhelming. I think it might be a mistake. It's a good invention, even if it produces terrible things like the atomic bomb... I was in Buenos Aires when the first man set foot on the moon and someone stopped me on the street and said, enthusiastically: We landed on the moon. We, the people. Neither the Russians nor the Americans.

MS: You love Jules Verne, Welles... And you’ve dreamed with them.

JLB: Yes, they regarded science and the future with great courage.

MS: How did you manage to convince Welles to lend you his time machine? (He smiles.) There’s only a tiny step from their science to poetry... I would like you to talk about your poetry. I’ve translated some of your poems in Romanian...

JLB: (He gives me a long look.) Hope you’ve improved them... I don't care much for my poetry.

MS: I left them as they were.

JLB: My poems? They are fragments, scraps. I think poetry, in general, is no less mysterious than music. Maybe it is even more mysterious. Music consists of sounds. In poetry there are sounds but also ideas, intimations... I am not a poet. Just an old man trying to be a poet. If I had to choose among the poets I like... But why choose one, when there are so many? I don't like eloquence. Things are always the same: love, memory, hope, forgetting. What’s important is what you do with them, with the experience. At times I get the feeling that something is going to happen. What I see when I write is the beginning and the end—I don't know what happens in-between—and I wait. When I was young I believed in metaphors. Now I’m convinced each subject comes with its own aesthetics.

MS: Is there a link between the musicality of a language and the musicality of intimations found in poetry? I believe that all languages are suitable for poetry. It’s unfortunate, however, that not all of them enjoy the same circulation.

JLB: In my youth I tried to learn French, which I speak quite badly. (It's a figure of speech, of course. Our dialogue takes place in Voltaire's language and his French is perfect.) Then I moved on to German, read Hölderlin, Heine... Started studying English.

MS: Well you can’t say you feel too bad in Spanish.

JLB: Maybe it isn’t my favorite language. Nowadays Maria Kodama is teaching me Japanese.

MS: I know. You also counted the steps in Japanese...

JLB: I am old and blind, and all I have left is the exorcism of literature… Language is a poetic tradition... All poets are important for the creation of this tradition... Of course, their importance is not equal, but they all have their place...

MS: When learning a foreign language, we acquire it with this halo of spirituality, of grace, not sure what to call it, created by poets using it, nurturing it, polishing it. And I for one am drawn, at first, by the mystery inherent in the poems of an unknown language. I learn it so that I can pronounce the sounds, the rhymes in their original form. You tend to use many of your own words in your poems. This creates difficulties in translation, especially when it comes to classical verse.

JLB: Indeed. But that's how they come.

MS: Whitman, for example, is also full of proper names... For him, they are rather landmarks. In your poetry, words like Spinoza, Urbina are, I guess, metaphors—they have the value of building blocks. Your lyric means erudition—but an erudition in a state of poetic emanation... Erudition dislodged from its place, its position. Like a rock that rolls over and remains fixed on the edge of a precipice. Restless, inquisitive, an erudition lost... in the labyrinth.

JLB: Perhaps it's another way of referring to myself. Caesar wrote the war against the Gauls in the third person. He didn't say: I did this, but: "Alors, le brave est arrivé". (Laughing) The brave was him. People are very proud.

MS: Like poets... Do you believe in inspiration?

JLB: I always have the feeling I receive thoughts as a gift. Poe believed they were an intellectual invention. He was wrong, although he was a great poet. When I write, I often have to choose between two verses: one is what I want to say, the other is more euphonic.

MS: You choose the more euphonic one.

JLB: Precisely. I choose the word that’s less true to my thinking, but more true to the euphony.

MS: Which doesn’t happen in your prose.

JLB: No. I try to render thinking exactly, or as accurately as possible.

MS: Does creation grant you a balance?

JLB: When I don't write, I feel guilty. My fatum is to write. If I don't write I feel culpable.

MS: This state of culpability is creative.

JLB: You can’t find something without searching for it. Give memory a chance. Poetry must create itself. Secretly, underground.

MS: There is talk of certain obsessions in your work. The tango, the dagger, the labyrinth, the tiger. Like heraldic signs of a lyric dynasty with a single representative.

JLB: Those I didn't look for. The tiger obsession, for example. I could have used "leopard" or "jaguar". But I chose tiger. Chesterton called it "a symbol of awful elegance". And, after a few moments: "an emblem of awful elegance"...

MS: I was really impressed by the speech you gave at the congress inauguration. I liked the tension of the phrases, the overt way, so to speak, in which you present your work. You attempt to minimize it, shroud it in a sort of gloom of failure. I had the chance to listen to you another time, in Morelia, in Mexico, and after that in Ciudad de Mexico. You were saying you weren’t even a writer; that your writing was a simulacrum. On the other hand, what stands out in everything you put down on paper is precisely the great importance you attach to literature, to the word, to culture as chance for humanity. The manner in which you follow dead languages, fossil cultures, disappearing practices, the fate of a Celtic or Icelandic word. This whole tide of spirituality that pulsates in your pages seems auspicious to me. An exemplary tension for writers.

JLB: If libraries burn down, new ones will be built. Other writers will emerge—a new Homer, a new Virgil. Different than them, of course. Our destiny is nostalgic. Literature begins with poetry and reaches prose with great difficulty. I hope my name will be forgotten. My poems too.

MS: Why, Mr. Borges?

He looks up in my direction again. His eyes are always clear, sky-blue.

JLB: This is also a wish.

There’s a knock at the door, a discreet sign I shouldn't tire him too much. I close my notebook, in which I only wrote down a few of the things my interlocutor said.

Besides, the author of The Book of Sand likes to talk, waits for opportunities to be questioned, he’s a rare prey (for reporters), the fact of being hunted offers him a kind of pleasure. The solitude of his blindness is compensated by a continuous monologue-dialogue with himself. However, he doesn’t often do interviews. Doing one with me caused quite a stir among my friends here.

MS: Say, in relation to the importance of words in a verse. You always change a word or two in successive editions of poems. By studying these changes, one can see the nodal points of the poem. The poem is like a Chinese map of the body's nerve centers. Inserting, from place to place, a new word, you give lyricism a kind of acupuncture.

JLB: The word is indeed very important in a verse. I always have the impression I use the tritest one.

MS: Did you like what Carranza said: "Poetry is a non-economic, contemplative activity" which opposes "technology’s delusional ambition".

JLB: Nevertheless, technology took us to the moon!

MS: You say somewhere: "For a true poet, every moment of life, every fact should be intensely poetic, since deep down it is the actual truth." Do you experience everything as intensely?

JLB: Maybe I had some privileged moments. I wrote a lot in my youth, so that I have something to redact now.

MS: You consider poetry the fruit of a desire, not a fulfillment. Desire, longing, suffering make up the engine of inspiration—or, seeing as we’re near the Sahara, its camel... What is it you have always wished for?

JLB: Desires also change.

MS: Do they change all by themselves or do we contribute to them changing as well?

JLB: They’re landscapes seen from a moving train. Motion always refreshes them—but eventually one can perceive the monotony.

MS: You wouldn't be able to sit still. Your travel speed is amazing... It's as if you were in several places at the same time. You carry around the globe an entire library. Many of the books, so to speak, obvious. But in fact the covers of some conceal your own works. Do you read your favorite authors to find yourself?

JLB: I have very good friends, ancients and moderns.

MS: In your speech you quoted lines from a Persian poet, some from an Asian author, about the Himalayas, and a stanza from Shakespeare. You said: "these metaphors, found centuries ago, and in different places, are still valid today".

JLB: I made a point of saying that because some poets today confuse poetry with politics.

We go down, with brief stops, to the conference room in the basement of the large Marrakesh Hotel.

JLB: (Resting) Why did they make the room so deep?

MS: To inearth poetry. Sepulcher it.

At the press conference that concludes the congress, the great poet stands leaning on his cane, at the presidium's table, reflecting, listening to the exchanges between journalists and poets. He then leaves without saying a word. He’s seen wandering in the Jamaa El Fna square, accompanied by Maria Kodama, listening to stories from One Thousand and One Nights in the shadow of the al-Kutubiyya mosque, standing behind a snake charmer. He knows the cobra by the intensity of the tamer's music.

Borges—a character by Borges. Always on the move, able to deceive cardinal points and time zones in search of "analogies between dissimilar things"—the definition Aristotle uses for metaphor, or "the absolute caught in the moment."

An Argentinian poet shared an amusing anecdote about his phenomenal spontaneity once. They were dining out together when a journalist, instead of inquiring about Milton, Keats, or Chesterton, asked him what he thought of the rice which had just been served. Borges looked at him a moment and replied: It's great! Each grain of rice has kept its individuality.

In his answers, actual fragments and scraps of prose, each word uttered by Borges does not crumble against the others but keeps its individuality intact.

He raises his clear eyes and looks at me, as if really seeing me. It's morning. Marrakesh sends a yellowish Sahara light into the hotel room—the sunrise multiplied on sand crystals and filtered through very tall palm trees that come all the way up to the window.

Jorge Luis Borges: I dreamed I was in a hotel in Buenos Aires, in the southern part of the city. And when I woke I heard the muezzin. Do you know what it says?

MS: "There is only one God and Muhammad is his prophet."

JLB: Yes, that's what I heard. And I realized I’m not in Buenos Aires. One sleeps well in Africa... There’s a wildlife park somewhere around here... I fell asleep thinking I’d hear roars...

MS: Of blue tigers? Of the enchanted stones of the High Atlas Mountains? How do you like this morning? Do you like mornings?

JLB: Yes, because they give the illusion of a beginning. They make you think something begins again. But that is false.

MS: And yet we enjoy being deceived this way...

JLB: Indeed, there is complicity in this illusion. After I have my coffee, however, I feel fine.

MS: I believe the interview is a strange animal and it could possibly make an appearance in your book of fantastic animals. A kind of Bahamut, made out of two different breaths, half visible and half invisible. Resting on an answer and carrying a question on its back. I’d like our animal to be more answer though. The fatality of always being asked about your writing will function this time too. Do you accept it?

JLB: Yes.

MS: I didn't prepare any questions. When we were going down to the conference room yesterday, I heard you counting the steps out loud. There were several series of stairs, like in your stories. You were counting each flight in a different language. You were descending as if down a mystery you had visited before. I thought then to ask you about labyrinths—figured the obsession with labyrinths would be a good question for Borges. Besides, everyone asks it.

JLB: I’ve just been to Crete. They made me doctor honoris causa. Instead of helping me understand the Cretan labyrinth better, they made me doctor honoris causa in it. In the labyrinth. (He laughs.) This labyrinth obsession is old. Because I’ve always felt lost. And this loss is the labyrinth…

MS: Maybe that's why you travel so much... To find yourself in the world... Has anyone made a map of your travels?

JLB: No.

MS: You are fascinated by the root of things, the root of words. The labyrinth is perhaps the root of a stone tree. That's why you feel enticed by it, because it’s a root.

JLB: The word "labyrinth" is a triumph in itself. An ingenious word. I want to write a poem about Theseus. The labyrinth is always there and we are in the labyrinth. It was built by someone. The labyrinth is a center and one feels lost—as I always do—at the center. But the universe is not a labyrinth. It's chaos. Day, night, the four seasons— they all make us believe that everything that surrounds us isn’t chaos, that there is a secret cosmos. And that we could find Ariadne’s thread.

MS: Is it possible?

JLB: I don't know. We have to look for it. Someone said finding a solution is not that important. It is important to search. To search forever. To search, always, even without hope. Poetry is an attempt at orientation—in the world—like science is. When we talk about technology, and this happens all the time, we talk about it as if it was something overwhelming. I think it might be a mistake. It's a good invention, even if it produces terrible things like the atomic bomb... I was in Buenos Aires when the first man set foot on the moon and someone stopped me on the street and said, enthusiastically: We landed on the moon. We, the people. Neither the Russians nor the Americans.

MS: You love Jules Verne, Welles... And you’ve dreamed with them.

JLB: Yes, they regarded science and the future with great courage.

MS: How did you manage to convince Welles to lend you his time machine? (He smiles.) There’s only a tiny step from their science to poetry... I would like you to talk about your poetry. I’ve translated some of your poems in Romanian...

JLB: (He gives me a long look.) Hope you’ve improved them... I don't care much for my poetry.

MS: I left them as they were.

JLB: My poems? They are fragments, scraps. I think poetry, in general, is no less mysterious than music. Maybe it is even more mysterious. Music consists of sounds. In poetry there are sounds but also ideas, intimations... I am not a poet. Just an old man trying to be a poet. If I had to choose among the poets I like... But why choose one, when there are so many? I don't like eloquence. Things are always the same: love, memory, hope, forgetting. What’s important is what you do with them, with the experience. At times I get the feeling that something is going to happen. What I see when I write is the beginning and the end—I don't know what happens in-between—and I wait. When I was young I believed in metaphors. Now I’m convinced each subject comes with its own aesthetics.

MS: Is there a link between the musicality of a language and the musicality of intimations found in poetry? I believe that all languages are suitable for poetry. It’s unfortunate, however, that not all of them enjoy the same circulation.

JLB: In my youth I tried to learn French, which I speak quite badly. (It's a figure of speech, of course. Our dialogue takes place in Voltaire's language and his French is perfect.) Then I moved on to German, read Hölderlin, Heine... Started studying English.

MS: Well you can’t say you feel too bad in Spanish.

JLB: Maybe it isn’t my favorite language. Nowadays Maria Kodama is teaching me Japanese.

MS: I know. You also counted the steps in Japanese...

JLB: I am old and blind, and all I have left is the exorcism of literature… Language is a poetic tradition... All poets are important for the creation of this tradition... Of course, their importance is not equal, but they all have their place...

MS: When learning a foreign language, we acquire it with this halo of spirituality, of grace, not sure what to call it, created by poets using it, nurturing it, polishing it. And I for one am drawn, at first, by the mystery inherent in the poems of an unknown language. I learn it so that I can pronounce the sounds, the rhymes in their original form. You tend to use many of your own words in your poems. This creates difficulties in translation, especially when it comes to classical verse.

JLB: Indeed. But that's how they come.

MS: Whitman, for example, is also full of proper names... For him, they are rather landmarks. In your poetry, words like Spinoza, Urbina are, I guess, metaphors—they have the value of building blocks. Your lyric means erudition—but an erudition in a state of poetic emanation... Erudition dislodged from its place, its position. Like a rock that rolls over and remains fixed on the edge of a precipice. Restless, inquisitive, an erudition lost... in the labyrinth.

JLB: Perhaps it's another way of referring to myself. Caesar wrote the war against the Gauls in the third person. He didn't say: I did this, but: "Alors, le brave est arrivé". (Laughing) The brave was him. People are very proud.

MS: Like poets... Do you believe in inspiration?

JLB: I always have the feeling I receive thoughts as a gift. Poe believed they were an intellectual invention. He was wrong, although he was a great poet. When I write, I often have to choose between two verses: one is what I want to say, the other is more euphonic.

MS: You choose the more euphonic one.

JLB: Precisely. I choose the word that’s less true to my thinking, but more true to the euphony.

MS: Which doesn’t happen in your prose.

JLB: No. I try to render thinking exactly, or as accurately as possible.

MS: Does creation grant you a balance?

JLB: When I don't write, I feel guilty. My fatum is to write. If I don't write I feel culpable.

MS: This state of culpability is creative.

JLB: You can’t find something without searching for it. Give memory a chance. Poetry must create itself. Secretly, underground.

MS: There is talk of certain obsessions in your work. The tango, the dagger, the labyrinth, the tiger. Like heraldic signs of a lyric dynasty with a single representative.

JLB: Those I didn't look for. The tiger obsession, for example. I could have used "leopard" or "jaguar". But I chose tiger. Chesterton called it "a symbol of awful elegance". And, after a few moments: "an emblem of awful elegance"...

MS: I was really impressed by the speech you gave at the congress inauguration. I liked the tension of the phrases, the overt way, so to speak, in which you present your work. You attempt to minimize it, shroud it in a sort of gloom of failure. I had the chance to listen to you another time, in Morelia, in Mexico, and after that in Ciudad de Mexico. You were saying you weren’t even a writer; that your writing was a simulacrum. On the other hand, what stands out in everything you put down on paper is precisely the great importance you attach to literature, to the word, to culture as chance for humanity. The manner in which you follow dead languages, fossil cultures, disappearing practices, the fate of a Celtic or Icelandic word. This whole tide of spirituality that pulsates in your pages seems auspicious to me. An exemplary tension for writers.

JLB: If libraries burn down, new ones will be built. Other writers will emerge—a new Homer, a new Virgil. Different than them, of course. Our destiny is nostalgic. Literature begins with poetry and reaches prose with great difficulty. I hope my name will be forgotten. My poems too.

MS: Why, Mr. Borges?

He looks up in my direction again. His eyes are always clear, sky-blue.

JLB: This is also a wish.

There’s a knock at the door, a discreet sign I shouldn't tire him too much. I close my notebook, in which I only wrote down a few of the things my interlocutor said.

Besides, the author of The Book of Sand likes to talk, waits for opportunities to be questioned, he’s a rare prey (for reporters), the fact of being hunted offers him a kind of pleasure. The solitude of his blindness is compensated by a continuous monologue-dialogue with himself. However, he doesn’t often do interviews. Doing one with me caused quite a stir among my friends here.

MS: Say, in relation to the importance of words in a verse. You always change a word or two in successive editions of poems. By studying these changes, one can see the nodal points of the poem. The poem is like a Chinese map of the body's nerve centers. Inserting, from place to place, a new word, you give lyricism a kind of acupuncture.

JLB: The word is indeed very important in a verse. I always have the impression I use the tritest one.

MS: Did you like what Carranza said: "Poetry is a non-economic, contemplative activity" which opposes "technology’s delusional ambition".

JLB: Nevertheless, technology took us to the moon!

MS: You say somewhere: "For a true poet, every moment of life, every fact should be intensely poetic, since deep down it is the actual truth." Do you experience everything as intensely?

JLB: Maybe I had some privileged moments. I wrote a lot in my youth, so that I have something to redact now.

MS: You consider poetry the fruit of a desire, not a fulfillment. Desire, longing, suffering make up the engine of inspiration—or, seeing as we’re near the Sahara, its camel... What is it you have always wished for?

JLB: Desires also change.

MS: Do they change all by themselves or do we contribute to them changing as well?

JLB: They’re landscapes seen from a moving train. Motion always refreshes them—but eventually one can perceive the monotony.

MS: You wouldn't be able to sit still. Your travel speed is amazing... It's as if you were in several places at the same time. You carry around the globe an entire library. Many of the books, so to speak, obvious. But in fact the covers of some conceal your own works. Do you read your favorite authors to find yourself?

JLB: I have very good friends, ancients and moderns.

MS: In your speech you quoted lines from a Persian poet, some from an Asian author, about the Himalayas, and a stanza from Shakespeare. You said: "these metaphors, found centuries ago, and in different places, are still valid today".

JLB: I made a point of saying that because some poets today confuse poetry with politics.

We go down, with brief stops, to the conference room in the basement of the large Marrakesh Hotel.

JLB: (Resting) Why did they make the room so deep?

MS: To inearth poetry. Sepulcher it.

At the press conference that concludes the congress, the great poet stands leaning on his cane, at the presidium's table, reflecting, listening to the exchanges between journalists and poets. He then leaves without saying a word. He’s seen wandering in the Jamaa El Fna square, accompanied by Maria Kodama, listening to stories from One Thousand and One Nights in the shadow of the al-Kutubiyya mosque, standing behind a snake charmer. He knows the cobra by the intensity of the tamer's music.

Borges—a character by Borges. Always on the move, able to deceive cardinal points and time zones in search of "analogies between dissimilar things"—the definition Aristotle uses for metaphor, or "the absolute caught in the moment."

An Argentinian poet shared an amusing anecdote about his phenomenal spontaneity once. They were dining out together when a journalist, instead of inquiring about Milton, Keats, or Chesterton, asked him what he thought of the rice which had just been served. Borges looked at him a moment and replied: It's great! Each grain of rice has kept its individuality.

In his answers, actual fragments and scraps of prose, each word uttered by Borges does not crumble against the others but keeps its individuality intact.

|

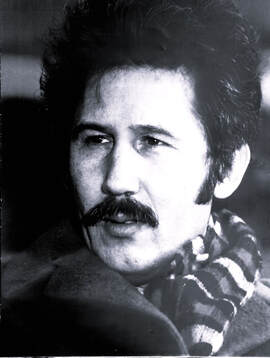

Interview available for the first time in English (translation © Daniel Nemo) by kind permission of the Marin Sorescu Foundation. Original text first published in Tratat de Inspirație by Marin Sorescu (Scrisul Românesc, 1985).

|

|

Daniel Nemo is an Amsterdam-based poet, translator, and photographer.

More info at www.danielnemo.com |